Updated on 2025/04/15. Go to meta.

Inspired by Lesser known

tricks, quirks and features of C.

To generate this .html out of cpp_tips_tricks_quirks.md, run Pandoc:

pandoc -s --toc --toc-depth=4

--standalone

--number-sections

--highlight=kate

--from markdown --to=html5

--lua-filter=anchor-links.lua

cpp_tips_tricks_quirks.md

-o cpp_tips_tricks_quirks.htmlwhere anchor-links.lua is the only customization for # links in sections.

C++ reference:

Here, kv is a COPY instead of const reference since

std::meow_map value_type is

std::pair<const Key, T>, notice const

Key.

pair<std::string, int> is copy-constructed from

pair<const std::string, int> . Proper version:

Note, AAA

style (Almost Always Auto) recommends to go with

const auto& that also solves the problem (sadly, with

the loss of explicitly written types):

with C++17 structured binding, it’s also:

See /u/STL comments. Note on /u/STL meow.

Surprisingly, you can declare a function with using declaration:

using MyFunction = void (int);

// same as `void Foo(int)`. NOT a variable

MyFunction Foo;

// actual definition

void Foo(int)

{

}Notice, Foo is not a variable, but function

declaration. Running the code above with

clang -Xclang -ast-dump, shows:

`-FunctionDecl 0xcc10e50 <line:4:1, col:12> col:12 Foo 'MyFunction':'void (int)'

`-ParmVarDecl 0xcc10f10 <col:12> col:12 implicit 'int'Same can be done to declare a method:

struct MyClass

{

using MyMethod = void (int, char);

// member function declaration

MyMethod Bar;

// equivalent too:

// void Bar(int);

};

// actual definition

void MyClass::Bar(int)

{

}Mentioned at least there. See also:

typedef double MyFunction(int, double, float);

MyFunction foo, bar, baz; // functions declarations

// OR

int foo(char), bar();Access rights are resolved at compile-time, virtual function target - at run-time. It’s perfectly fine to move virtual-override to private section:

class MyBase

{

public:

virtual void Foo(int) {}

// ...

};

class MyDerived : public MyBase

{

private:

// note: Foo is private now

virtual void Foo(int v) override {}

};

void Use(const MyBase& base)

{

base.Foo(42); // calls override, if any

}

Use(MyDerived{});It (a) clean-ups derived classes public API/interface (b) explicitly signals that function is expected to be invoked from within framework/base class and (c) does not break Liskov substitution principle.

In heavy OOP frameworks that rely on inheritance (Unreal Engine, as an example), it makes sense to make virtual-overrides protected instead of private so derived class could invoke Super:: version in the implementation.

See cppreference. Specifically, to handle exceptions for constructor initializer:

int Bar()

{

throw 42;

}

struct MyFoo

{

int data;

MyFoo() try : data(Bar()) {}

catch (...)

{

// handles the exception

}

};but also works just fine for regular functions to handle arguments construction exceptions:

public when derivingMinor, still, see cppreference, access-specifier:

struct MyBase {};

struct MyDerived1 : MyBase {}; // same as : public MyBase

class MyDerived2 : MyBase {}; // same as : private MyBase(void)0 to force ; (semicolon) for

macrosTo be consistent and force the user of the macro to put

; (semicolon) at the line end:

#define MY_FOO(MY_INPUT) \

while (true) { \

MY_INPUT; \

break; \

} (void)0

// ^^^^^^

MY_FOO(puts("X"));

MY_FOO(puts("Y"));See also Accessing template base class members in C++.

Given standard code like this:

we can call Base::Foo() with no issues. However, in case

when we use templates, Foo() can’t be found. The trick is to use

this->Foo(). Or MyBase<U>::Foo():

template<typename T>

struct MyBase { void Foo(); };

template<typename U>

struct MyDerived : MyBase<U>

{

void Bar() { this->Foo(); }

};this->Foo() becomes type-dependent

expression.

= default on implementationYou can default special member functions in the .cpp/out of line definition:

Note, this is almost the same as = default in-place, but makes constructor user-defined. Sometimes it’s not a desired side effect. However, it’s nice in case you want to change the body of constructor later or put breakpoint (since you don’t need to change header and recompile dependencies, only .cpp file).

Another use-case is to move destructor to .cpp file so you don’t delete incomplete types:

struct MyInterface; // forward-declare

struct MyClass

{

std::unique_ptr<MyInterface> my_ptr;

~MyClass();

};

// myclass.cpp

#include "MyInterface.h" // include only now

MyClass::~MyClass() = default; // generate a call to my_ptr.~unique_ptr()= delete for free functionsYou can delete unneeded function overload anywhere:

MyHandle('x') does not compile now, see std::ref,

std::as_const

for the use in STL.

#line and file renamingSee cppreference:

wich outputs:

output.s: any_filename.x:777: int main(): Assertion

falsefailed.

Note: this could break .pdb(s).

Bonus: what happens if you do #line 4294967295?

To not repeat code inside const and non-const function, see SO:

struct MyArray

{

char data[4]{};

const char& get(unsigned i) const

{

assert(i < 4);

return data[i];

}

char& get(unsigned i)

{

return const_cast<char&>(static_cast<const MyArray&>(*this).get(i));

}

};Note: mutable get() is implemented in terms of const

version, not the other way around (which would be UB).

Kind-a outdated with C++23’s Deducing this or is it? (template, compile time, .h vs .cpp).

std:: and why it still compiles (ADL)Notice, that code below will compile (most of the time):

std::vector<int> vs{6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1};

sort(vs.begin(), vs.end()); // note: missing std:: when calling sort()Since std::vector iterator lives in namespace std:: (*),

ADL will be performed to find std::sort and use it. ADL = Argument-dependent

lookup (ADL), also known as Koenig lookup.

(*) Note, iterator could be just raw pointer (int*) and

it’s implementation defined (?) where or not iterator is inside std.

Meaning the code above is not portable (across different implementations

of STL).

::std::move everywhere?Take a look at MSVC’s implementation of the C++ Standard Library:

_STD _Seek_wrapped(_First, _STD move(_UResult.in));

return {_STD move(_First), _STD move(_UResult.fun)};_STD is #define _STD ::std::. Why?

So ::std::move is used to disable ADL

and make sure implementation of move from namespace

std is choosen. Who knows what user-defined custom type

could bring into the table?

TBD

If class derives from enable_shared_from_this:

shared_from_this() in constructor is not

safe anyway.Hence, provide Create() factory function to encode the

behavior:

struct MyData : public std::enable_shared_from_this<MyData>

{

public:

static std::shared_ptr<MyData> Create()

{

// Quiz: why not std::make_shared?

return std::shared_ptr<MyData>(new MyData{});

}

private:

explicit MyData() = default;

};See cppreference example. Most-likely, you also want class copy/move ctor/assignments to be deleted.

std::shared_ptr aliasing constructorSee aliasing constructor:

struct MyType

{

int data;

};

std::shared_ptr<MyType> v1 = std::make_shared<MyType>();

std::shared_ptr<int> v2{v1, &v1->data};v2 and v1 now share the same control block. You can also put a pointer to unrelative data (is there real-life use-case?).

dynamic_cast<void*> to get most-derived

objectFrom anywhere in the hierarhy of polimorphic type, you can restore a

pointer to most-derived instance (i.e., the one created by

new initially):

struct MyBase { virtual ~MyBase() = default; };

struct MyDerived : MyBase {};

MyDerived* original_ptr = new MyDerived{};

MyBase* base_ptr = original_ptr;

void* void_ptr = dynamic_cast<void*>(base_ptr);

assert(void_ptr == original_ptr);See cppreference. Most-likely useful to interop with C library/external code.

std::shared_ptr<base> with no virtual

destructorUsually, if you delete pointer-to-base, destructor needs to be declared virtual so proper destructor is invoked. Hovewer, for std::shared_ptr this is not required:

struct MyBase { ~MyBase(); }; // no virtual!

struct MyDerived : MyBase

{

~MyDerived() { std::puts("~MyDerived()"); }

};

{

std::shared_ptr<MyBase> ptr = std::make_shared<MyDerived>();

} // invokes ~MyDerived()std::shared_ptr<MyBase> holds MyBase*

pointer, but has type-erased

destroy function that remembers the actual type it was created with.

See also GotW #5, Overriding Virtual Functions:

Make base class destructors virtual

This works and a and b have different values:

See, for instance, Revisiting Stateful Metaprogramming in C++20:

Self-contained example from How to Hack C++ with Templates and Friends:

template<int Private::* Member>

struct Stealer {

friend int& dataGetter(Private& iObj) {

return iObj.*Member;

}

};

template struct Stealer<&Private::data>;

int& dataGetter(Private&); //redeclare in global ns

// ...

Private obj;

dataGetter(obj) = 31; // OkSee this for more details.

See, this or cppreference.

Allows to declare some set of template instantiations and actually intantiate them in another place. Usually, you extern template in the header and instantiate in your own/library .cpp file:

// myvector.h

template<typename T>

class MyVector { /**/ };

// declare frequently used instantiations

extern template class MyVector<int>;

extern template class MyVector<float>;

extern template class MyVector<char>;

// myvector.cpp

#include "myvector.h"

// instantiate frequent cases **once**;

// client needs to link with myvector.o

template class MyVector<int>;

template class MyVector<float>;

template class MyVector<char>;C++ had also never implemeted C++98 export keyword (C++98, nothing to do with modules).

It’s usually stated that templates could only be defined in header file. However, you just need to define them anywhere so definition is visible at the point of use/instantiation.

For intance, this works just fine:

// myclass.h

class MyClass

{

public:

int Foo();

private:

template<typename T>

int Bar();

};

// myclass.cpp

// template class, defined in this .cpp file

template<typename U>

struct MyHelper {};

template<typename T>

int MyClass::Bar()

{

// definition of member-function-template Bar();

// also, the use of MyHelper template above,

// visible only to this transtlation unit

return sizeof(MyHelper<T>{});

}

int MyClass::Foo()

{

// use of function template

return Bar<char>();

}See also extern templates.

If you have template class that has template member function and you want to define such function out-of-class, you need:

template<typename T1, typename T2>

class MyClass

{

template<typename U>

void Foo(U v);

};

template<typename T1, typename T2> // for MyClass

template<typename U> // for Foo

void MyClass<T1, T2>::Foo(U v) {}When implementors do use memcopy/memmove to construct/assign range of

values for some user-defined type T? Use

std::is_trivially_* type traits to query

the property:

struct MyType

{

int data = -1;

char str[4]{};

};

int main()

{

MyType v1{42};

MyType v2{66};

static_assert(std::is_trivially_copy_assignable<MyType>{});

std::memcpy(&v1, &v2, sizeof(v1)); // fine

assert(v1.data == 66);

}Overall, see also std::uninitialized_* memory management and std::copy algorithm and/or analogs that are already optimized for trivial/pod types by your standard library implementation for you.

In generic context, it’s possible to invoke the destructor of int:

which is no-op. See destructor and built-in member access operators. Exists so you don’t need to special-case destructor call in generic/template code.

In the same way you can call destructor manually, you can call constructor:

alignas(T) unsigned char buffer[sizeof(T)];

T* ptr = new(static_cast<void*>(buffer)) T; // call constructor

ptr->~T(); // call destructorwhich is placement new.

Note on the use of static_cast<void*> - while not

needed in this example, it’s needed to be done in generic context to

avoid invoking overloaded version of new, if any.

See cppreference. In short, every class has its own name inside the class itself. Which happens to apply recursively. This leads to surprising syntax noone uses:

struct MyClass

{

int data = -1;

void Foo();

};

int main()

{

MyClass m;

// access m.data

m.MyClass::data = 4;

assert(m.data == 4);

// now with recursion

m.MyClass::MyClass::MyClass::data = 7;

assert(m.data == 7);

// call a member function

MyClass* ptr = &m;

ptr->MyClass::Foo();

}For templates, this allows to reference class type without specifying template arguments.

template<typename T, typename A>

struct MyVector

{

// same as Self = MyVector<T, A>

using Self = MyVector;

};Given an instance of derived class, one can skip invoking its own function override and call parent function directly (see injected-class-name):

struct MyBase

{

virtual void Foo()

{ std::puts("MyBase"); }

};

struct MyDerived : MyBase

{

virtual void Foo() override

{ std::puts("MyDerived"); }

};

int main()

{

MyDerived derived;

derived.MyBase::Foo();

MyDerived* ptr = &derived;

ptr->MyBase::Foo();

}This will print MyBase 2 times since we explicitly call

MyBase::Foo().

See class rvalue trick discussed there;

see same trick discussed in guaranteed

copy elision in C++17.

In short, we can return non-copyable/non-movable type from a function:

struct Widget

{

explicit Widget(int) {}

Widget(const Widget&) = delete;

Widget& operator=(const Widget&) = delete;

Widget(Widget&&) = delete;

Widget& operator=(Widget&&) = delete;

};

Widget MakeWidget()

{

return Widget{68}; // works

}

int main()

{

Widget w = MakeWidget(); // works

}However, how to construct, let say

std::optional<Widget>? That does not work:

int main()

{

std::optional<Widget> o1{MakeWidget()}; // does not compile

std::optional<Widget> o2;

o2.emplace(MakeWidget()); // does not compile

}The trick is to use any type that has implicit conversion operator:

struct WidgetFactory

{

operator Widget()

{

return MakeWidget();

}

};

int main()

{

std::optional<Widget> o;

o.emplace(WidgetFactory{}); // works

}See, for instance, What’s the deal with std::type_identity? or dont_deduce<T>. In short, this will not compile:

template<typename T>

void Process(std::function<void (T)> f, T v)

{

f(v);

}

int main()

{

Process([](int) {}, 64);

}We try to pass a lambda that has unique type X which has nothing to

do with std::function<void (T)>. Compiler does not

know how to deduce T from X.

Here, we want to ask compiler to not deduce anything for parameter

f:

template<typename T>

void Process(std::type_identity_t<std::function<void (T)>> f, T v)

{

f(v);

}

int main()

{

Process([](int){}, 64);

}T is deduced from 2nd argument, std::function is constructed from a given lamda as it is.

From priority_tag for ad-hoc tag dispatch and CppCon 2017: Arthur O’Dwyer “A Soupcon of SFINAE”.

Here, we convert x to string trying first x.stringify()

if that exists, otherwise std::to_string(x) if that works

and finally fallback to ostringstream as a final resort:

#include <string>

#include <sstream>

template<unsigned I> struct priority_tag : priority_tag<I - 1> {};

template<> struct priority_tag<0> {};

template<typename T>

auto stringify_impl(const T& x, priority_tag<2>)

-> decltype(x.stringify())

{

return x.stringify();

}

template<typename T>

auto stringify_impl(const T& x, priority_tag<1>)

-> decltype(std::to_string(x))

{

return std::to_string(x);

}

template<typename T>

auto stringify_impl(const T& x, priority_tag<0>)

-> decltype(std::move(std::declval<std::ostream&>() << x).str())

{

std::ostringstream s;

s << x;

return std::move(s).str();

}

template<typename T>

auto stringify(const T& x)

{

return stringify_impl(x, priority_tag<2>());

}You can leave type dedcution to the compiler when using new:

From cppreference:

double* x = new double[]{1, 2, 3}; // creates an array of type double[3]

auto p = new auto('c'); // creates a single object of type char.

// p is a char*

auto q = new std::integral auto(1); // OK: q is an int*

auto r = new std::pair(1, true); // OK: r is a std::pair<int, bool>*std::forward use in std::function-like caseMost of the times, we say that std::forward should be used in the context of forwarding references that, usually, look like this:

v is forwarding reference specifically because T&& is used and T is template parameter of Process function template.

However, classic example would be std::function call operator() implementation:

template<typename Ret, typename... Types>

class function<Ret (Types...)>

{

Ret operator()(Types... Args) const

{

return Do_call(std::forward<Types>(Args)...);

}

};

// usage

function<void (int&&, char)> f; // (1)

f(10, 'x'); // (2)where user specifies Types at (1) that has nothing to do

with operator() call at (2) which is not even a function

template now.

If you run reference

collapsing rules over possible Types and

Args, std::forward is just right.

See GotW #5, Overriding Virtual Functions:

Never change the default parameters of overridden inherited functions

Going more strict: don’t have virtual functions with default arguments.

struct MyBase

{

virtual void Foo(int v = 34);

};

struct MyDerived : MyBase

{

virtual void Foo(int v = 43);

};

MyBase* ptr = new MyDerived;

ptr->Foo(); // calls MyDerived::Foo, but with v = 34 from MyBasedefault arguments are resolved at compile time, override function target - at run-time; may lead to confusion.

See GotW #5, Overriding Virtual Functions:

When providing a function with the same name as an inherited function, be sure to bring the inherited functions into scope with a “using” declaration if you don’t want to hide them

Going more strict: avoid providing overloads to virtual

functions.

For modern C++: use override

specifier.

struct MyBase

{

virtual int Foo(char v) { return 1; }

};

struct MyDerived : MyBase

{

virtual int Foo(int v) { return 2; }

};

int main()

{

MyDerived derived;

return derived.Foo('x');

}main is going to return 2 since MyDerived::Foo(int) is

used. To use MyBase::Foo(char):

struct MyDerived : MyBase

{

using MyBase::Foo; // add char overload

virtual int Foo(int v) { return 2; }

};Note: bringing base class method with using declation is,

potentially, a breaking change (see above, derived.Foo('x')

now returns 1 instead of 2).

See Using-declaration. You can make protected member to be public in derived class:

struct MyBase

{

protected:

int data = -1;

};

struct MyDerived : MyBase

{

public:

using MyBase::data; // make data public now

};It’s observed that, often, class API has .Reset() function (even more often when two phase initialization is used):

If your API is anything close to modern C++ and supports value semantics, just have move assignment implemented with default constructor, which leads to:

See also “default constructor is a must for modern C++”

What happens with the object after the move? The known answer for C++ library types is that it’s in “valid but unspecified state”. Note, that for most cases in practice, the object is in empty/null state (see Sean Parent comments) or, to say it another way - you should put the object into empty state to be nice.

Why it’s in “empty” state? Simply because destructor still runs after the move and we need to know whether or not it’s needed to free resources most of the times:

struct MyFile

{

int handle = -1;

// ...

~MyFile()

{

if (handle >= 0)

{

::close(handle);

handle = -1;

}

}

MyFile(MyFile&& rhs) noexcept

: handle(rhs.handle)

{

rhs.handle = -1; // take ownership

}

}For a user or even class author, it’s also often needed to check if the object was not moved to ensure correct use:

Now, should the class expose is_valid() API? Maybe,

maybe not; up to you. More elegant solution that requires smaller amount

of exposed APIs could be just a pair of default construction and

operator==:

Leaving validity check alone, any time you support move, just expose such state with default constructor. More often then not it makes life easier. See also “state reset”.

Relative: Move Semantics and Default Constructors - Rule of Six?.

Default constructor may be used as a fallback in a few places of STL/your code:

std::vector<MyData> v;

v.resize(1'000); // insert 1'000 default-constructed MyData elements

std::map<int, MyData> m;

m[1] = MyData{98}; // default construct MyData, then reassign

std::variant<MyData, int> v; // default construct MyDataFollowing C++ value semantic, move semantic with its empty state, it may also be used to reset state or check whether or not the instance is valid:

Default constructor should contain nothing except default/trivial data member initialization. Specifically, no memory allocations, no side effects.

Bonus question: why does this code allocates under MSVC debug?

Hint: MSVC STL debug iterators machinery.

Constructors (at least of objects for types that are part of your application domain) should just assign/default initialize data members, NO business/application logic inside. This applies to copy constructor, constructors with parameters, move constructor.

Simply because you don’t control when and who and how can invoke and/or ignore/skip your constructor invocation. See, for instance, (but not only) Copy elision/RVO/NRVO/URVO.

But what about RAII? How to make RAII classes then?

struct MyFile

{

public:

using FileHandle = ...;

static Open(const char* file_name)

{

FileHandle handle = ::open(file_name); // imaginary system API

return MyFile{handle};

}

explicit MyFile() noexcept = default;

~MyFile(); // ...

private:

explicit MyFile(FileHandle handle) noexcept

: file_handle{handle}

{

}

FileHandle file_handle{};

};Isn’t this makes sense only when exceptions are disabled? Not sure exceptions change anything there.

Sometimes I even leave MyFile(FileHandle handle)-like

constructors public. This makes API extremely hackable and testable.

std::unique_ptr with decltype lambdaSince C++20, with Lambdas in unevaluated contexts, you can have poor man’s scope exit as a side effect:

using on_exit = std::unique_ptr<const char,

decltype([](const char* msg) { puts(msg); })>;

void Foo()

{

on_exit msg("Foo");

} // prints Foo on scope exitfrom Creating a Sender/Receiver HTTP Server for Asynchronous Operations in C++.

auto vs auto* for pointersSince auto type deduction comes from template

argument deduction, it’s fine to have auto* in the same

way it’s fine to have T* as a template parameter:

auto p1 = new int; // p1 = int*

auto* p2 = new int; // p2 = int*

const auto p3 = new int; // p3 = int* const

const auto* p4 = new int; // p4 = const int*Still, note the difference for p3 vs p4 - const pointer to int vs just pointer to const int!

See Passing overload sets to functions:

#define FWD(...) \

std::forward<decltype(__VA_ARGS__)>(__VA_ARGS__)

#define LIFT(X) [](auto &&... args) \

noexcept(noexcept(X(FWD(args)...))) \

-> decltype(X(FWD(args)...)) \

{ \

return X(FWD(args)...); \

}

// ...

std::transform(first, last, target, LIFT(foo));tolower functionYou can’t take an adress of std:: function since the function could be implemented differently with different STL(s) and/or in the feature the function may change, hence such code is not portable. From A popular but wrong way to convert a string to uppercase or lowercase:

The standard imposes this limitation because the implementation may need to add default function parameters, template default parameters, or overloads in order to accomplish the various requirements of the standard.

So, strictly speaking, ignoring facts from the article, this is not portable C++:

operator new/operator delete can have global

replacement. Usually used to actually inject custom memory

allocator, but also is used for tracking/profiling purpose. And can be

used for debugging:

void* operator new(std::size_t size)

{

return malloc(size); // assume size > 0

}

void operator delete(void* ptr) noexcept

{

free(ptr);

}

int main()

{

std::string s{"does it allocate for this input?"};

// ...

}Just put a breakpoint inside your version of new/delete; observe callstack and all the useful context.

Hint: same can be done with, let say, WinAPI - use Detours.

std::shared_ptr<void> as user-data pointerstd::shared_ptr<void> holds void*

pointer, but also has type-erased

destroy function that remembers the actual type it was created with, so

this is fine:

std::shared_ptr<void> ptr1 = std::make_shared<MyData>(); // ok

std::shared_ptr<MyData> ptr2 = std::static_pointer_cast<MyData>(ptr1); // okSee Why

do std::shared_ptr

See sync_with_stdio.

In practice, this means that the synchronized C++ streams are unbuffered, and each I/O operation on a C++ stream is immediately applied to the corresponding C stream’s buffer. This makes it possible to freely mix C++ and C I/O.

In addition, synchronized C++ streams are guaranteed to be thread-safe (individual characters output from multiple threads may interleave, but no data races occur).

std::ios::sync_with_stdio(false);

std::cout << "a\n";

std::printf("b\n"); // may be output before 'a' above

std::cout << "c\n";Note: not the same as syncstream/C++20.

See also cin.tie(nullptr).

clog

cppreference and cerr. Associated

with the standard C error output stream stderr (same as

cerr), but:

Output to stderr via std::cerr flushes out the pending output on std::cout, while output to stderr via std::clog does not.

std::cout << "aaaaa\n";

std::clog << "bbbbb\n"; // may not flush "aaaaa"

std::cerr << "ccccc\n"; // flush "aaaaa"extern "C" void Handle(void (*MyCallback)(int));

Handle([](int V) { std::println("{}", V); }); // pass to C-function

void (*MyFunction)(int) = [](int) {}; // convert to C-functionIn case lambda has empty capture list (and no deducing this is used), it can be converted to c-style function pointer (has conversion operator). See lambda.

+[](){} to convert lambda to c-functionSee A positive lambda: ‘+’ - What sorcery is this?:

#include <functional>

void foo(std::function<void()> f) { f(); }

void foo(void (*f)()) { f(); }

int main ()

{

foo( [](){} ); // ambiguous

foo( +[](){} ); // not ambiguous (calls the function pointer overload)

}The + in the expression

+[](){}is the unary + operator […] forces the conversion to the function pointer type

In addition: what *[](){} does? And

+*[](){}?.

conversion function or cast operator is the same as regular function and could also be made virtual:

struct MyBase

{

virtual operator int() const

{ return 1; }

};

struct MyDerived : MyBase

{

virtual operator int() const override

{ return 2; }

};

void Handle(const MyBase& Base)

{

const int V = Base;

std::print("{}", V);

}

int main()

{

Handle(MyDerived{}); // prints 2

}Used to perfect-construct object in-place. Below is valid C++98:

#include <cassert>

#include <new>

// array of max size 2 for int(s) for illustation

struct MyArray

{

/*alignas(int)*/ char buffer[2 * sizeof(int)];

int size; // = 0;

void* emplace_back()

{

assert(size < 2);

void* memory = (buffer + size * sizeof(int));

size += 1;

return memory;

}

};

int main()

{

MyArray v;

new(v.emplace_back()) int(44);

new(v.emplace_back()) int(45);

}Observed in Unreal Engine:

operator-> recursion (returning non-pointer

type)If operator-> returns non-pointer type, compiler will

automatically invoke operator-> on returned value until

its return type is pointer:

std::vector<int> data; // for illustration purpose

struct A0

{

std::vector<int>* operator->() { return &data; }

};

struct A1

{

A0 operator->() { return A0{}; } // note: returns value

};

struct A2

{

A1 operator->() { return A1{}; } // note: returns value

};

int main()

{

A2 v;

v->resize(3); // finds A0::operator->()

}Used for arrow_proxy.

std::initializer_list with “uniform initialization” was introduced together with move semantics in C++11. However, surprisingly, initializer_list does not support move-only types like std::unique_ptr. This does not compile:

std::vector<std::unique_ptr<int>> vs{

std::make_unique<int>(1), std::make_unique<int>(2), std::make_unique<int>(3)

};The fix could be the use of temporary array in this case:

std::unique_ptr<int> temp[]{

std::make_unique<int>(1), std::make_unique<int>(2), std::make_unique<int>(3)

};

std::vector<std::unique_ptr<int>> vs{

std::make_move_iterator(std::begin(temp)),

std::make_move_iterator(std::end(temp))

};C++ initialization is famously complex. C++11 “uniform

initialization” with braces {} (list-initialization) is

famously non-uniform, see:

Sometimes also called as unicorn initialization; see also Forrest Gump C++ initialization.

Personal opinion - The best way is to fall back to ()

with C++ 20 Allow initializing

aggregates from a parenthesized list of values:

but also see C++20’s parenthesized aggregate initialization has some downsides.

Cheat sheet:

std::function was introduced together with move

semantics in C++11. However, surprisingly, std::function does not

support move-only lambda/function objects. This does not compile:

That’s one of the reasons C++23 std::move_only_function was introduced.

From std::functionand Beyond:

See also:

Since C++11, you can manually control lifetime of user-defined types. See Union declaration for more precise definition:

using String = std::string; // non-trivial type

union MyUnion

{

String s0;

String s1;

MyUnion() { new(&s0) String("aa"); } // activate s0

~MyUnion() { } // does not know what to destruct

};

int main()

{

MyUnion u;

u.s0.~String(); // free active member

new(&u.s1) String("bb"); // construct s1

// ...

u.s1.~String(); // clean-up

}You can omit capture of const/global data in a simple cases:

int MyGlobal = 98;

int main()

{

const int MyConst = 65;

auto lambda0 = []() { return MyGlobal; }; // ok

auto lambda1 = []() { return MyConst; }; // ok

}However, if const is odr-used (e.g., pointer is taken or reference-to is formed), it needs to be captured:

void Foo(const int*);

void Bar(const int&);

int main()

{

const int MyConst = 65;

auto lambda0 = []() { Foo(&MyConst); }; // error

auto lambda0 = []() { Bar(MyConst); }; // error

}See “implicit”/“odr-usable” in cppreference.

See 2 Lines Of Code and 3 C++17 Features - The overload Pattern.

C++17 version:

template<class... Ts> struct overload : Ts... { using Ts::operator()...; };

template<class... Ts> overload(Ts...) -> overload<Ts...>;

std::variant<int, float> vv{67};

std::visit(overload

{

[](const int& i) { std::cout << "int: " << i; },

[](const float& f) { std::cout << "float: " << f; }

},

vv);C++20 version:

C++23 version (see Visiting a std::variant safely):

template<class... Ts>

struct overload : Ts...

{

using Ts::operator()...;

// Prevent implicit type conversions

consteval void operator()(auto) const

{

static_assert(false, "Unsupported type");

}

};See When an empty destructor is required and Smart pointers and the pointer to implementation idiom.

In short, this does not compile:

// apple.h

class Orange;

class Apple {

std::unique_ptr<Orange> orange{};

};

// use (error)

Apple a{};since compiler-generated destructor is placed in the apple.h and

tries to invoke Orange destructor. Deleting incomplete type

is UB.

The fix is to move destructor definition to .cpp file:

// apple.h

class Orange;

class Apple {

std::unique_ptr<Orange> orange{};

~Apple();

};

// apple.cpp

Apple::Apple() = default;

// use (fine)

Apple a{};shared_ptr<const T>TBD: code sample

See Enough string_view to hang ourselves.

TBD: code sample

See I Have No Constructor, and I Must Initialize:

You’d expect the printed result to be 0, right? You poor thing. Alas—it will be garbage.

See, for instance, std::string_view

and std::map. std::meow_map has invariant and does not allow easily

modify keys, making value_type to be

std::pair<const Key, T>. Modifying it implicitly is

UB:

int main()

{

std::string s1 = "wwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww";

std::string s2 = "bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb";

std::map<std::string_view, int> m;

m[s1] = 1;

m[s2] = 2;

s1 = "xx"; // what's the state of map?

}This is also the reason std::owner_less/owner_hash/owner_equal exist. See Enabling the Use of weak_ptr as Keys in Unordered Associative Containers.

std::piecewise_constructSee also What’s up with std::piecewise_construct and std::forward_as_tuple?.

In case pair-like type has to:

To foward a set of arguments to a sigle constructor, then:

std::pair<int, MyIds> p2{std::piecewise_construct // for tag-dispatch

, std::tuple<int>(1) // first value

, std::tuple<int, int>(4, 6) // second value

};

// OR

std::pair<int, MyIds> p3{std::piecewise_construct // for tag-dispatch

, std::forward_as_tuple(1) // first value, from std::tuple<int&&>

, std::forward_as_tuple(4, 6) // second value, from std::tuple<int&&, int&&>

};This applies to std::meow_map, see emplace:

std::map<int, MyIds> my_map;

auto [_, inserted] = my_map.emplace(std::piecewise_construct

, std::forward_as_tuple(1)

, std::forward_as_tuple(4, 6));map[key] creates default-constructed value firstSee map::operator[]

which looks like this (simplifiyed) and returns T&

ALWAYS:

If key does not exist, no exception is thrown, instead

default-constructed value T is inserted:

std::map<int, std::string> my_map;

my_map[1]; // key 1 = empty string, inserted anyway

my_map[2] = "xxx"; // key 2 = empty string inserted,

// empty string re-assigned nextSee also “default constructor must do no work” and “const map[key] does not compile”.

map[key] does not compile, use .find()See “map[key] creates default-constructed value first”. Because

map::operator[] is:

you can’t use it for const map lookup, since operator at needs to insert default value in case key does not exist:

void MyProcess(const std::map<int, std::string>& kv)

{

const std::string& my_value = kv[42]; // does not compile

}if not map.find(x) then map[x] is an antipatternIn case you need to do extra work only if key does not exist, having code like this:

void MyProcess(std::map<int, std::string>& my_data)

{

auto it = my_data.find(56); // lookup #1

if (it != my_data.end())

{

my_data[56] = "data 56"; // lookup #2 then

// default construct & assign std::string

}

}Instead, insert or emplace key-value first:

void MyProcess(std::map<int, std::string>& my_data)

{

auto [it, inserted] = my_map.insert(56, std::string());

if (!inserted)

{

it->value = "data 56";

}

}(You can use emplace to avoid default-constructing std::string).

Relies on static local variables. Points to consider:

See also C++ and the Perils of Double-Checked Locking.

From Storage classes/static:

Starting in C++11, a static local variable initialization is guaranteed to be thread-safe. This feature is sometimes called magic statics. However, in a multithreaded application all subsequent assignments must be synchronized […]

struct MyClass

{

static MyClass& GetInstance()

{

static MyClass instance; // magic static

return instance;

}

};Note, that:

If control enters the declaration concurrently while the variable is being initialized, the concurrent execution shall wait for completion of the initialization

See also Double-Checked Locking is Fixed In C++11, meaning that you may pay for each call to GetInstance:

// MyClass& v1 = MyClass::GetInstance();

// MyClass& v2 = MyClass::GetInstance(); // may need to check

// guard/initialization anyway

movzx eax, BYTE PTR guard variable for MyClass::GetInstance()::instance[rip]

test al, al

je .L15

mov eax, OFFSET FLAT:MyClass::GetInstance()::instance

retA trick to avoid macro invocation.

You see code like this?

and wonder why anyone would put extra parentheses? Thanks to Windows.h we may have min and max available as MACROS, hence:

does not work. Extra parentheses around function name prevent macro invocation. Other workarounds include:

If you conrol build system, you may enforce WIN32_LEAN_AND_MEAN, NOMINMAX and heard about VC_EXTRALEAN.

It’s a trick to convert to bool.

Lets have a look at MSVC assert implementation:

expression comes from client/user code and may be of ANY

type, int, const char*, anything. !! is used

to silence any warning since || expects bool. First ! actually converts

to bool, second ! reverts value to original one.

Same happens in code like this:

Why not static_cast<bool>(x)? MSVC may warn you

about (bool)a, bool(a) and

static_cast<bool>(a). See also contextually

converted to bool.

sizeof v and sizeof(v)Turns out, for expression sizeof does not requre parentheses:

int v = 0;

const unsigned size = sizeof(v); // compiles

const unsigned size = sizeof v; // same as abovewhere sizeof(Type) requires parentheses for a type. See

sizeof

operator.

Ts......See C++11’s six dots:

is valid C++, where Ts... is “a function with a variable

number of arguments” and the next 3 dots ... is “a variadic

function from C, varargs”; all because comma is optional. From the

acticle above:

// These are all equivalent.

template <typename... Args> void foo1(Args......);

template <typename... Args> void foo2(Args... ...);

template <typename... Args> void foo3(Args..., ...);+Update: depracated, valid up until C++26, see The Oxford variadic comma:

Deprecate ellipsis parameters without a preceding comma. The syntax (int…) is incompatible with C, detrimental to C++, and easily replaceable with (int, …)

assert(x && "message")Used to print “message” when assert fails. Compare the output of:

and

bool x = false;

assert(x && "message");

// example.cpp:2: int main(): Assertion `x && "message"' failed.This works since “message” is implicitly converted to

const char* which then is converted to bool and is always

true. Because of that next variations exist to always fail, but with a

message:

<assert.h> and NDEBUG with no include guard<assert.h> and <cassert> are

special in the sense that there is no header include guard, by

design - see, for instance, MSVC implementation:

This is so you can ON and OFF NDEBUG whenever you want

and include <assert.h> to either get working

assert() or a no-op in a different parts of the program.

Consider:

// impl.cpp

#include <cassert>

void MyFoo()

{

assert(false); // may or may not trigger `assert()`;

// depends on compilation options

}

#if defined(NDEBUG)

# undef NDEBUG

#endif

#include <cassert> // include 2nd time, assert is ENABLED

void MyBar()

{

assert(false); // invokes std::abort(), always

}Usually useful for one-file tools to fail fast even in Release:

// main.cpp

#include "my_api.h"

#include <Windows.h>

#if defined(NDEBUG)

# undef NDEBUG

#endif

#include <cassert> // enable assert in Release also

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

assert(argc > 1 && "Expected single <file_name> argument passed");

const char* file_name = argv[1];

}The same thing:

From this SO answer:

Universal reference was a term Scott Meyers coined […] At the time the C++ standard didn’t have a special term for this, which was an oversight in C++11 and makes it hard to teach. This oversight was remedied by N4164 […]

See Universal References in C++11 and n4164/Forwarding References.

Even if arguments of constexpr function are known at compile time, it’s not guarantee that its going to be evaluated at compile time. To force constexpr run at compile time, need to use it in a context where compile time value is expected, such as template argument or constexpr variable:

constexpr int MyHash(const char* str) { return 9; }

template<int N>

struct ForceCompileTime

{

static int Get() { return N; }

};

int main()

{

int v1 = MyHash("v1"); // may run at run-time

constexpr int v2 = MyHash("v2"); // compile-time

int v3 = ForceCompileTime<MyHash("v3")>::Get(); // compile-time

}See also Epic’s Unreal Engine version: UE_FORCE_CONSTEVAL, where variable template is used instead.

See Non-terminal

variadic template parameters where apply_last is

showcased.

Specifically, arguments deduction does not work in cases like this:

template<typename... Args>

void Foo(Args..., int default_v = 10) { }

int main()

{

Foo(0.1f, 'c'); // does not compile

}You can, however, specify all Args… explicitly, so this works:

Usually, this is solved case by case. For instance, to emulate this kind of API:

template<typename... Args>

void WaitAll(Args&&... args, milliseconds timeout = milliseconds::max());TODO - show simple code snippet.

Something like this does not work (see this SO):

template <typename... Args>

void debug(Args&&... args,

const std::source_location& loc = std::source_location::current());Introducing type with implicit constructor is the trick:

#include <source_location>

#include <stdio.h>

struct FormatWithLocation {

const char* fmt;

std::source_location loc;

FormatWithLocation(const char* fmt_,

const std::source_location& loc_

= std::source_location::current())

: fmt(fmt_), loc(loc_) {}

};

template<typename... Args>

void debug(FormatWithLocation fmt, Args&&... args) {

printf("[%s:%d] ", fmt.loc.file_name(), fmt.loc.line());

printf(fmt.fmt, args...);

}

int main() { debug("hello %s %s", "world", "around"); }See also Non-terminal variadic template parameters.

See this SO:

template <typename... Ts>

struct debug

{

debug(Ts&&... ts

, const std::source_location& loc = std::source_location::current());

};

template <typename... Ts>

debug(Ts&&...) -> debug<Ts...>;

// debug(5, 'A', 3.14f, "foo"); // worksSee also Non-terminal variadic template parameters and “variadic template with default argument” section.

Sometimes it’s useful to know the type of a variable deep inside templates:

template<typename T> struct Show;

template<typename T>

void Foo(T&& v)

{

Show<decltype(v)>{};

}

Foo(10);Show is intentionally incomplete. Compiler will print

the error message like this:

error: invalid use of incomplete type 'struct Show<int&&>'

Show<decltype(v)>{};

^~~~and you can see that v has type

int&& there.

See also Template meta-programming: Some testing and debugging tricks.

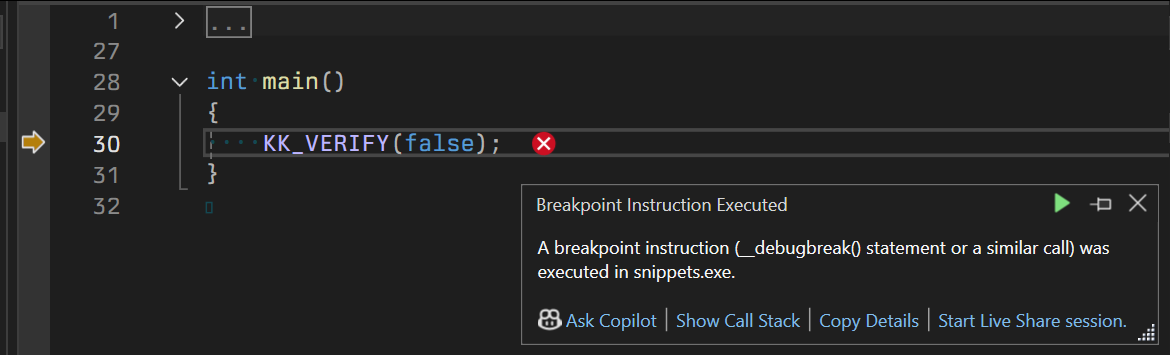

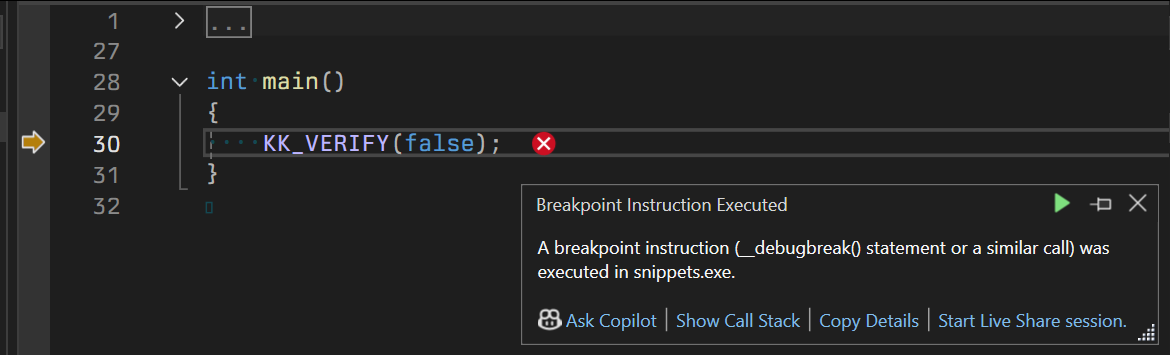

When custom version of assert is needed, it’s useful to inject

__debugbreak right at assert definition so you can get

breakpoint hit exactly at the location of the assert fail. In short:

#define KK_ABORT(KK_FMT, ...) (void) \

(::log_abort(__FILE__, __LINE__, KK_FMT, ##__VA_ARGS__), \

__debugbreak(), /*MSVC-specific*/ \

std::quick_exit(-1)) /*in case of non-debugbreak platforms*/

#define KK_VERIFY(KK_EXPRESSION) (void) \

(!!(KK_EXPRESSION) || \

(KK_ABORT("Verify failed: '%s'", #KK_EXPRESSION), false))__debugbreak() hits under debugger and points exactly at

assert/verify location:

Side question: why operator comma is used in

(KK_ABORT(...), false)?

, ##__VA_ARGS__ vs C++20

__VA_OPT__TBD. See SO, cppreference.

std::move(object) does not “move” on its own. So

Similarly, you can move into function that accepts rvalue refence. If function implementation does not actually modify/move argument - initial move is a no-op:

void Foo(std::string&& str) // rvalue reference

{

std::puts("not using str");

}

std::string str = ...

Foo(std::move(str)); // no-op

// str is unchanged, can be used freely,

// but only because you **know** exact implementation of `Foo`Same, if class has only copy constructor, copy assignment and no move constructor/move assignment, the code is no-op:

struct MyClass

{

MyClass(const MyClass& rhs) { /**/ }

MyClass& operator=(const MyClass& rhs) { /**/ }

};

MyClass object;

MyClass copy = std::move(object); // no-op or rathe copy constructor is invoked

// object is unchaged, can be used freelySame, if class has move constructor/move assignmed that actually does not use/or modify argument, it is no-op again:

struct MyClass

{

MyClass(MyClass&& rhs) { std::puts("not using rhs actually"); }

MyClass& operator=(const MyClass& rhs) { std::puts("same"); }

};

MyClass object;

MyClass o2 = std::move(object); // no-op, even tho move constructor was invoked

// object is unchaged, can be used freelySo in short std::move is a cast to rvalue that is used only for overload resolution; only to select move constructor instead of copy constructor if both present, etc.

See C++ Rvalue References Explained web archive (July 2024).

After std::move object still alive and invokes destructor.

TODO

See On harmful overuse of std::move.

TODO

const T&& (const rvalue)rvalue is still a REFERENCE, const rvalue can be formed in the same way as normal const lvalue:

void Foo(const int&) { std::puts("(const int&)"); }

void Foo(int&) { std::puts("(int&)"); }

void Foo(int&&) { std::puts("(int&&)"); }

void Foo(const int&&) { std::puts("(const int&&)"); }

int main()

{

const int v = 72;

Foo(std::move(v)); // (const int&&)

}Here, we accidentaly move const object, so cast to

const int&& happens.

Overloads with const T&& references are usually deleted, see std::ref, std::as_const:

See SO discussion on usefullness.

Does below compile?

Yes. Exactly the same as enum class MyEnum.

#include <cstio>

enum class MyEnum

{

MyValue0 = 0,

MyValue1 = 1,

MyValue2 = 2,

};

void MyProcess(MyEnum v)

{

using enum MyEnum;

switch (v)

{

case MyValue0: std::puts("got MyValue0"); break;

case MyValue1: std::puts("got MyValue1"); break;

case MyValue2: std::puts("got MyValue2"); break;

}

// Note: no need to fully-qualify MyEnum::MyValue0.

}Note, however, this is not going to work for template class member function:

template<typename T>

struct MyType

{

enum class MyEnum { X };

void Foo()

{

using enum MyEnum;

}

};errors out with:

error: ‘using enum’ of dependent type ‘MyType

::MyEnum’

see specialize a template class member without specializing whole class for an explanation.

See using declaration and using directives.

namespace MyNamespace

{

void Foo();

void Bar();

}

using MyNamespace::Bar; // using declaration

Bar();

using namespace MyNamespace; // using directive

Foo();One brings single name; another brings whole namespace.

dynamic_cast<T*> and

dynamic_cast<T&>One returns nullptr on fail, the other one throws std::bad_cast:

struct Base

{

virtual ~Base() = default;

};

struct Derived : Base {};

void Handle(Base* base)

{

Derived* d_ptr = dynamic_cast<Derived*>(base);

assert(d_ptr); // null on fail

try

{

Derived& d_ref = dynamic_cast<Derived&>(*base);

}

catch (const std::bad_cast&)

{

assert(false); // exception of fail

}

}dynamic_cast<const T*> adds conststruct V {};

void Handle(V* v)

{

const V* v1 = dynamic_cast<const V*>(v);

const V* v2 = static_cast<const V*>(v);

const V* v3 = const_cast<const V*>(v);

}Usually, it’s said that dynamic_cast needs to be appliyed to

polymorphic type, note V in this case is not a polymorphic type (but

still a class type). See also

dynamic_cast<void*>.

Notice, `const_cast<const V*>`` can also be used to add const, not only remove it.

CONOUT$, CONIN$ for

::AllocConsole()See Console Handles. In case you do ::AllocConsole(), you may want to reinitialize C and C++ stdio:

// /SUBSYSTEM:WINDOWS or Not Set.

int WINAPI wWinMain(HINSTANCE, HINSTANCE, PWSTR, int)

{

KK_VERIFY(::AllocConsole());

FILE* unused = nullptr;

KK_VERIFY(0 == freopen_s(&unused, "CONOUT$", "w", stdout));

KK_VERIFY(0 == freopen_s(&unused, "CONOUT$", "w", stderr));

KK_VERIFY(0 == freopen_s(&unused, "CONIN$", "r", stdin));

std::cout.clear(); // to reset badbit/failbit

std::clog.clear();

std::cerr.clear();

std::cin.clear();

return 0;

}See this SO for std::wcout and friends reinitilization.

In case you just need a file content as std::string:

std::string ReadFileAsString(const char* file_path)

{

std::ifstream file{file_path};

KK_VERIFY(file);

std::ostringstream ss;

ss << file.rdbuf();

KK_VERIFY(ss);

std::string content = std::move(ss).str();

return content;

}Is it “fast” enough?

See also rdbuf:

int main()

{

std::ifstream in("in.txt");

KK_VERIFY(in);

// redirect std::cin to in.txt

std::streambuf* old_cin = std::cin.rdbuf(in.rdbuf());

KK_VERIFY(old_cin);

std::ofstream out("out.txt");

KK_VERIFY(out);

// redirect std::cout to out.txt

std::streambuf* old_cout = std::cout.rdbuf(out.rdbuf());

KK_VERIFY(old_cout);

// read/write

std::string word;

std::cin >> word;

std::cout << word;

std::cin.rdbuf(old_cin); // rollback

std::cout.rdbuf(old_cout);

}When adding new enum value to existing enum what places need to be updated?

// MSVC: /we4062

// Clang/GCC: -Werror=switch-enum

enum class MyEnum { E1, E2, E3, };

int MyProcess(MyEnum v)

{

switch (v)

{

case MyEnum::E1: return 1;

case MyEnum::E2: return 2;

// note: missing case MyEnum::E3 <-----

// note: default must not be present

}

}MSVC has Compiler

Warning C4062 to detect the issue. To make this warning as error,

use /we4062 which shows:

error C4062: enumerator 'E3' in switch of enum 'MyEnum' is not handled

note: see declaration of 'MyEnum'For Clang/GCC, it’s -Wswitch-enum

(note, -Wswitch exists) in a combination with

-Werror OR -Werror=switch-enum to error out

only switch case, similar to what MSVC’s /we4062 does:

error: enumeration value 'E3' not handled in switch [-Werror=switch-enum]See also this SO.

Note, usual practice of having COUNT or MAX

enum value - complicates the matter and forces you to handle undesired

case. With C++17, the usual code for handling all cases looks next:

#include <utility>

enum class MyEnum { E1, E2, MAX };

const char* MyProcess(MyEnum e)

{

switch (e)

{

case MyEnum::E1: return "E1";

case MyEnum::E2: return "E2";

case MyEnum::MAX: std::unreachable();

}

std::unreachable();

}Just use a wrong type first, see what compiler says, copy the correct type from the error:

All 3 compilers say:

Clang: error: cannot initialize a variable of type 'int'

with an rvalue of type 'int MyClass::*'

GCC : error: cannot convert 'int MyClass::*' to 'int' in initialization

MSVC : error C2440: 'initializing': cannot convert from

'int MyClass::*' to 'int'So ptr should be:

int MyClass::*ptr = &MyClass::my_data;

// OR

using MyIntMember = int MyClass::*;

MyIntMember ptr = &MyClass::my_data;Same works for member function pointers, etc.

With C++17, for instance, it’s possible to initialize enum with integer that does not match any named enum value:

enum byte : unsigned char {};

byte b{42}; // OK as of C++17

enum class MyEnum { E1, E2, };

MyEnum e{76}; // OKmeaning that even with all handled cases, it’s possible to fall out of switch case:

enum class MyEnum { E1, E2, };

const char* MyProcess(MyEnum e)

{

switch (e)

{

case MyEnum::E1: return "E1";

case MyEnum::E2: return "E2";

}

// perfectly fine to land there,

// even when compiled with -Werror=switch-enum

return "<unknown>"; // OR std::unreachable()

}

MyProcess(MyEnum{78}); // perfectly fineSee https://gist.github.com/maddouri/e22288fe973e107abf5bb775df84779d:

TBD

{

FILE* f = fopen("file.txt", "r");

ON_SCOPE_EXIT { fclose(f); }

// ...

}For C-style variadic function, each argument of integer type undergoes integer promotion, and each argument of type float is implicitly converted to the type double. See Implicit conversions:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdarg.h>

void MyFoo(int start, ...)

{

va_list args;

va_start(args, start);

const double v1 = va_arg(args, double);

const int v2 = va_arg(args, int);

printf("va_args: %f, %i\n", v1, v2);

va_end(args);

}

MyFoo(0, 3.3f, 'c');

// va_args: 3.300000, 993.3f of type float is conveted to double;

'c', which is char is converted to int so this is why

va_arg(args, double) is used to query v1.

Note, that va_arg(args, float) will at least trigger a

warning:

> warning: second argument to 'va_arg' is of promotable type 'float';

> this va_arg has undefined behavior because arguments will

> be promoted to 'double' [-Wvarargs]From std/over.call.object:

int f1(int);

char f2(float);

typedef int (*fp1)(int);

typedef char (*fp2)(float);

struct A {

operator fp1() { return f1; }

operator fp2() { return f2; }

} a;

int i = a(1); // calls f1 via pointer

// returned from conversion function

char c = a(0.5f); // calls f2To get size/length/count of c-style static array pre-C++17 constexpr std::size(), next ARRAY_SIZE macro is used:

// no definition needed

template <typename T, unsigned N>

char (&ArraySizeHelper(T (&array)[N]))[N];

#define ARRAY_SIZE(array) \

(sizeof(ArraySizeHelper(array)))

int data[4]{};

int copy[ARRAY_SIZE(data)]; // ARRAY_SIZE(data) = 4, known at compile timeCompared to “usual” ((sizeof(a) / sizeof(*(a)))

definition, ARRAY_SIZE does not allow some missuses (like passing

pointers). See old

chromium changelist. Epic’s Unreal Engine has exactly the same

UE_ARRAY_COUNT macro.

Note, with C++17, std::size() should be used instead.

Note, also, how ArraySizeHelper is a function that accepts reference to array of size N (known at compile time) and returns reference to array of size N.

*f has type of reference-to-function:

void (&)()f has type of just function-type:

void()&f has type of pointer-to-function:

void (*)()Function (name), reference-to-function decay to function pointer

implicitly as soon as possible. *f forms a

reference-to-function, but then immediately decayed to

pointer-to-function which then gets converted back to reference

**f and so on.

See Pointers to functions, Function-to-pointer conversion and Function declaration.

In the context of Static Initialization Order Fiasco where global objects constructors from different ~.cpp files (translation units) are invoked in unspecified order, Schwarz Counter helps to be sure global object is initialized before the first use:

// my_object.h

struct MyObject {

int x;

MyObject(const char* src, int v);

};

extern MyObject& o1;

struct MyInit {

MyInit();

~MyInit();

};

// NOTE: static in the header -

// each transtlation unit will get its own copy of my_init.

static MyInit my_init;

// o1.cpp

#include "my_object.h"

#include <new>

static int counter = 0;

static alignas(MyObject) char data[sizeof(MyObject)];

// reference to not-yet-initialized memory

MyObject& o1 = reinterpret_cast<MyObject&>(data);

MyInit::MyInit() {

if (counter++ == 0) {

// first initialization

new (data) MyObject{"o1", 865};

}

}

MyInit2::~MyInit2() {

if (--counter == 0) {

o1.~MyObject();

}

}

// main.cpp

#include "my_object.h" // NOTE: must be included before the use

// use o1 anywhere in any global. OKNote on unspecified order: it’s usually .obj files link order. Consider MyObject class, where 2 objects are defined in o1.cpp and o2.cpp files:

// cl o1.cpp o2.cpp main.cpp && o1.exe

[o1 %0xa0ae40]

[o2 %0xa0ae54]

// cl o2.cpp o1.cpp main.cpp && o2.exe

[o2 %0xa0ae40]

[o1 %0xa0ae54]o1 is initialized first, then comes o2, when linking o1.cpp, o2.cpp. Swapping link options to o2.cpp, o1.cpp changes the order (interestingly, memory locations stay the same).

See More C++ Idioms/Nifty Counter.

Note: MSVC STL (and others?) does not use the idiom (relies on runtime linked first? TBD).

Note: may not work in case of precompiled headers use, see bug report.

From Kris Jusiak, godbolt:

template<class T>

concept Fooable = requires(T t) { t.foo; };

template<auto Concept>

struct foo {

auto fn(auto t) {

static_assert(requires { Concept(t); });

}

};

int main() {

struct Foo {

int foo{};

};

struct Bar {};

foo<[](Fooable auto){}> f{}; // NOTE: here

f.fn(Foo{});

f.fn(Bar{}); // static_assert, contrained not satisfied

}See On leading underscores and names reserved by the C and C++ languages. From Raymond Chen:

| Pattern | Conditions |

|---|---|

| Begins with two underscores | Reserved |

| Begins with underscore and uppercase letter | Reserved |

| Begins with underscore and something else | Reserved in global scope (includes macros) |

| Contains two consecutive underscores | Reserved in C++ (but okay in C) |

Note that:

popular convention of prefixing private members with an underscore is fine:

probably because of ambiguity, there is convention to postfix

size_ for members

the double-underscore reservation is the only one that isn’t well motivated anymore: It was originally because the CFront mangling of namespace separators/class separators was __ (see this reddit post)

See this reddit comment. NOT portable (godbolt):

#include <stdio.h>

class Class final { private: void function(); };

void Class::function() { puts("Called"); }

// Expose mangled name; fine for Clang and GCC.

// MSVC encodes with leading ? (?function@Class@@AEAAXXZ)

// which is disallowed identifier name

extern "C" void _ZN5Class8functionEv(Class*);

int main() {

Class c;

_ZN5Class8functionEv(&c);

}You can inject std::source_location into all coroutines

customization points to get information on where coroutine is

created/suspended/awaited/etc, see godbolt:

struct co_task

{

struct promise_type

{

co_task get_return_object(std::source_location loc

= std::source_location::current()) noexcept

{

print("get_return_object", loc);

return {};

}

// ...

struct awaitable

{

bool await_ready(std::source_location loc

= std::source_location::current())

{

print("await_ready", loc);

return false;

}

// ...

};

auto await_transform(int)

{

return awaitable{};

}

};

};

co_task co_test()

{

co_await 1;

co_return;

}which outputs:

get_return_object : '/app/example.cpp'/'co_task co_test()'/'63'

initial_suspend : '/app/example.cpp'/'co_task co_test()'/'63'

await_ready : '/app/example.cpp'/'co_task co_test()'/'65'

await_suspend : '/app/example.cpp'/'co_task co_test()'/'65'

await_resume : '/app/example.cpp'/'co_task co_test()'/'65'

return_void : '/app/example.cpp'/'co_task co_test()'/'66'

final_suspend : '/app/example.cpp'/'co_task co_test()'/'63'Originally comes from reading boost.cobalt.

Moved-from std::optional x still holds value after a

move:

Move-constructor of std::optional does not reset x, just

moves the value out of it. This is by definition of std::optional and

the general rule of “valid but unspecified state” does not apply in this

case, see optional.ctor:

constexpr optional(optional&& rhs) noexcept(see below);

// Postconditions: rhs.has_value() == this->has_value().People expect moved-from optional to have no value, i.e., as if

x = std::nullopt after a move, see “Beware when

moving a std::optional!” article (which has wrong conclusions and

solution) and this reddit

discussion.

set-new-and-check-old value in one go:

See Ben Deane “std:: exchange Idioms” talk and “std::exchange Patterns” article.

Has nothing to do with atomic::exchange().

For quick-and-dirty (but 100% correct) code to generate comparison operator with multiple members:

struct Person

{

std::string name;

int age = 0;

};

inline bool operator<(const Person& lhs, const Person& rhs) noexcept

{

return std::tie(lhs.name, lhs.age) <

std::tie(rhs.name, rhs.age);

}std::tie forms

std::tuple<const std::string&, const int&>;

std::tuple has generic implementation for operator<.

Same could be done for operator==. Is it an outdated idiom with spaceship operator (default comparisons) since C++20? Probably. See also this article.

Consider

extern std::set<int> vs;

bool was_inserted = false;

std::tie(std::ignore, was_inserted) = vs.insert(42);vs.insert() returns pair, std::tie here forms a tuple

with a reference to was_inserted, effectively having

assigning of

tuple<X, bool&> = pair<X, bool>. Note, how

std::ignore is used as poor man’s _

placeholder.

With C++17 structure bindings, same could be done:

Note, _ here is a usual variable, nothing special (up

until C++26, see A nice placeholder

with no name).

For a class with inline data, most of the time, data needs to be copied during the move. Consider:

struct MyBuffer

{

char data[1024]{};

MyBuffer(const MyBuffer& rhs) // copy

{

std::copy(std::begin(rhs.data), std::end(rhs.data)

, std::begin(data));

}

MyBuffer(MyBuffer&& rhs) // move. SAME as copy

{

std::copy(std::begin(rhs.data), std::end(rhs.data)

, std::begin(data));

}

};Our move constructor is exactly the same as copy constructor. There is no way to “steal” the data in a cheap way. See also std::move() Is (Not) Free.

This also hints that moving small std::string(s) (usually <= 15 chars) is the same as copying them since inline buffer because of SSO needs to be copied anyway.

It’s valid to forward-declare a type as an argument to a template:

template<typename Tag>

struct Tagged {};

using T1 = Tagged<struct Tag1>; // *

using T2 = Tagged<class Tag2_Any>;

// Note: Tag1, Tag2_Any are available to use, as if forward-declared:

extern Tag1* Foo(Tag2_Any*);see SO explanation.

Usually used in a template-heavy generic libraries to quickly introduce unique type, hence, “tagging” (TODO: find an example).

__PRETTY_FUNCTION__ (Clang, GCC) and

__FUNCSIG__ (MSVC) give a string with type names included

if used for a template:

#include <cstdio>

template<class T>

constexpr const char* Name()

{

#if defined(_MSC_VER)

return __FUNCSIG__;

#else

return __PRETTY_FUNCTION__;

#endif

}

int main()

{

std::puts(Name<int>());

}prints:

constexpr const char* Name() [with T = int]

^^^^^^^^^This is abused to parse a string, at compile time, to get type name out of it. Examples: StaticTypeInfo, magic_enum, lexy.

Similarly to __PRETTY_FUNCTION__ as compile time type

name, __PRETTY_FUNCTION__/__FUNCSIG__

could be used to generate a hash for a type at compile time, see, for

instance, this

SO:

template<typename T>

constexpr std::size_t Hash()

{

#ifdef _MSC_VER

#define F __FUNCSIG__

#else

#define F __PRETTY_FUNCTION__

#endif

std::size_t result = 0;

for (const char& c : F)

(result ^= c) <<= 1;

return result;

#undef F

}

template <typename T>

constexpr std::size_t constexpr_hash = Hash<T>();

// usage

constexpr std::size_t f = constexpr_hash<float>;

constexpr std::size_t i = constexpr_hash<int>;Notes:

but could be good enoug for known environments.

A trick to use global static counter and static local for a template to generate type id once:

inline unsigned& Global_Seq()

{

static unsigned counter = 1;

return counter;

}

template<typename T>

struct Id

{

static const unsigned id;

static unsigned Get() { return id; }

};

template<typename T>

/*static*/ const unsigned Id<T>::id = ++Global_Seq();

// usage

std::printf("int = %u\n", Id<int>::Get());

std::printf("char = %u\n", Id<char>::Get());Could be made simpler with inline variable and variable template, see, for instance, C++ tricks: type IDs.

Notes:

Global_Seq() must be static local to avoid

initialization order fiascobut could be made good enough for specific use-case.

From this reddit comment:

template<typename T>

struct MyType

{

enum class MyEnum

{

Option1,

Option2,

};

MyEnum v{};

};

// note: specialize **only** MyEnum

template<>

enum class MyType<int>::MyEnum

{

Surprise,

Anything,

};

void Foo(MyType<int> o1, MyType<char> o2)

{

switch (o1.v)

{

case MyType<int>::MyEnum::Surprise: ;

}

switch (o2.v)

{

case MyType<char>::MyEnum::Option1: ;

}

}without completely specializing whole class, we specialize only enum.

MyType still has MyEnum v data member for both cases, but

with completely different enum values.

See also using enum declaration.

See The Power of Hidden Friends in C++. Friend function for a class X:

In short:

struct X{

X(int){}

friend void foo(X){};

};

int main(){

X x(42);

foo(x); // OK, calls foo defined in friend declaration

foo(99); // Error: foo not found, as int is not X

::foo(x); // Error: foo not found as ADL not triggered

}Hence, foo() is a hidden friend. If, foo(X)

is declared in the enclosing namespace of X, normal lookup will find

it:

diff -r aaa\x.txt bbb\x.txt

> struct X;

> void foo(X); // namespace scope

< foo(99); // Error: foo not found, as int is not X

< ::foo(x); // Error: foo not found as ADL not triggered

> foo(99); // ok now

> ::foo(x); // ok nowThe benefits are:

See also “Hidden Friends and Enumerations” section from article above.

See also hidden friend idiom. From stdexec/MAINTAINERS.md:

For a class template instantiation such as N::S<A,B,C>, the associated entities include the associated entities of A, B, and C

Basically, ADL makes it so that functions associated with a type A

could be found even when A is a template argument. This is made,

probably, so something like std::reference_wrapper<A>

works (see “associated entities of class types” from p2822r1):

namespace ABC

{

struct A

{

friend void Foo(A)

{ std::puts("Foo(A)!"); } // Here

};

}

int main()

{

ABC::A o;

std::reference_wrapper<ABC::A> r{o};

Foo(r); // prints 'Foo(A)!'

}observe how hidden Foo() was found for the argument of

std::reference_wrapper<ABC::A> since

std::reference_wrapper got associated entities of its

argument type ABC::A.

From stdexec document above:

To avoid that problem, we take advantage of a curious property of nested classes: they don’t inherit the associated entities of the template parameters of the enclosing template

this is what struct __t for in the source

code of stdexec.

From the discussion of How can I choose a different C++ constructor at runtime? from Raymond Chen:

struct MyBase

{

MyBase(); // 1

MyBase(int v); // 2

MyBase(const MyBase& rhs); // 3

};

struct MyDerived : MyBase

{

MyDerived()

: MyBase(Make(42)) {} // **

static MyBase Make(int v)

{

return MyBase(v);

}

};Note how MyDerived default constructor can invoke ANY

available MyBase constructor, not only default one, but

also any other parent class constructor.

This is similar to the case when move or copy constructor can invoke parent’s default constructor, not only “desired” move or copy base constructor:

MyDerived(const MyDerived& rhs)

: MyBase() // default constructor

{

// any other required initialization

this->v_ = rhs.v_;

}Note, that MyBase(Make(42)) does not perform (otherwise

mandatory) copy elision, see this SO, that have this

comment

from Richard Smith:

this is a known bug in the language rules, and the tentative solution is that guaranteed copy elision doesn’t apply for a base class initializer

See: